Mark McManus, Managing Director at Stiebel Eltron, looks at why the capital has such a high percentage of energy-inefficient homes and what can be done about it now.

The government has invested millions into making the capital a sustainable place to live. With world-leading public transport, ongoing investment into clean and renewable energy, and increasing efforts to increase green space, the city’s credentials are always improving. Yet London’s housing is some of the most inefficient across the UK.

London’s population grows around 1.5% every year and today nearly nine million people call the city their home. According to figures from Statista, this growth is showing no signs of slowing either, with the population numbers expected to increase by another 1.2 million people by 2041, putting increasing pressure on city planners to ensure housing provision can meet the ongoing rising demand.

For the most part, inner city living can be a sustainable option for those looking to curb their carbon emissions. Efficient public transport means fewer single vehicles on the road, new housing tends to have a higher energy efficiency rating, and having amenities within close proximity to homes means more places can be accessed by foot.

London continues to invest significant sums into making the capital a green city too. It boasts more than 3,000 parks and green spaces and recently ranked 11th globally for its environmental sustainability as a result.

Despite this effort, there continues to be one key area that lowers London’s sustainability credentials – housing. London is famed for the architecture of its housing and it’s become a key part of the city’s charm. Yet a quarter of its housing falls into E, F, or G energy ratings. To put this into perspective, only 8% of the housing in the city of Salford falls into the same categories.

These energy efficiency ratings don’t just impact single family housing (terraced housing, detached, semi-detached) either. London’s high-rise buildings could be improved too.

Research from UCL’s Energy Institute found that high rise buildings are much more energy intensive than low-rise buildings. It found that energy usage is nearly two and a half times greater in high-rise buildings of 20 or more storeys than in low-rise buildings of six storeys or less.

Due to their scale, improving the energy efficiency of high-rise buildings is not an easy task. But there are simple short-term changes that can be made to instantly improve their sustainability credentials.

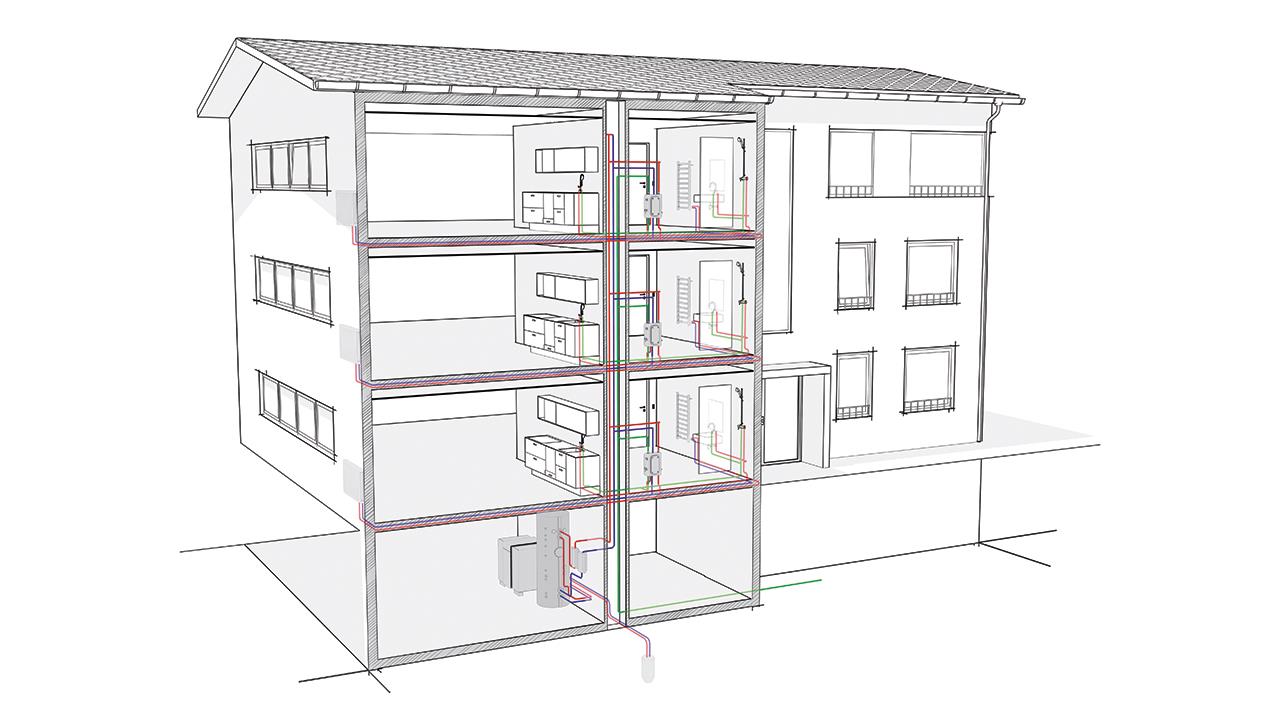

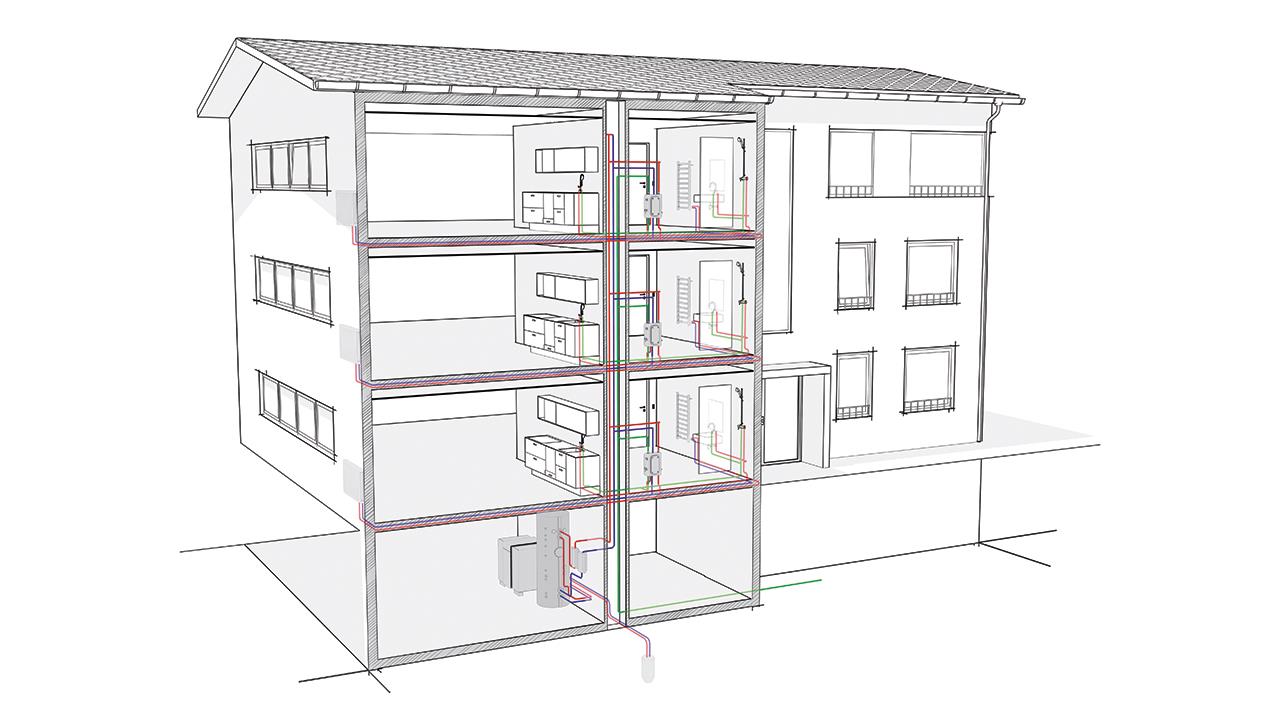

One such method is changing the way in which high-rise buildings are heated. A large number of London’s high-rise residential developments are currently heated using gas-fired centralised systems, which are inefficient in how they’re powered and also in how they disperse heat.

If only one flat in an entire building needs hot water, gas-fired systems will often need to circulate heat throughout the entire development to provide that water. This also means that significant heat is lost throughout the pipe network as the water travels upwards, leaving flats located on lower levels often uncomfortably hot for residents – a key concern in the recent Future Buildings Standard consultations.

There are a range of alternatives to gas-fired systems for high-rise developments on the market, which can improve resident comfort while significantly reducing energy usage at the same time.

Air source, ground source, and water-sourced heat pumps, for example, are a great alternative. Heat pumps tend to have a 300% efficiency rating, in comparison to 85% for traditional gas-fired boilers. They also produce no CO2, have cheaper operating costs, a faster heating speed, and a longer lifespan.

When installed in a high-rise development along with a heat interface unit in each apartment and an instantaneous hot water system, it means the water temperature can be boosted in the individual apartment at the time it is required – significantly reducing energy wastage.

Small changes like the way in which water is heated can make a significant impact on the energy efficiency of a buildings.

And, in a city like London which has already invested so much into making other areas of the capital green, housing should now become a key priority for the city if it’s to compete on a global stage for being a sustainability leader.

If you'd like to keep up-to-date with the latest developments in the heating and plumbing industry, why not subscribe to our weekly newsletters? Just click the button below and you can ensure all the latest industry news and new product information lands in your inbox every week.