Kevin O’Leary, Business Manager Heating Products at Samsung Climate Solutions, provides a detailed overview of why heat pumps must be a key pillar in the UK’s zero carbon goals.

Decarbonising heating is one of the biggest challenges we face in the UK, and one of the most important. If our journey to zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 is to be successful, then it is essential that we end our reliance on fossil fuels for heating and hot water production.

The government’s Ten Point Plan for a Green Industrial Revolution, introduced in November 2020, highlights heat pumps as a key technology for achieving this goal.

The plan sets the ambition of 600,000 heat pump installations per year by 2028.

These heat pumps will take their electrical power from the UK’s increasingly green grid. National Grid estimates that by 2030, 90% of the electricity it carries will come from zero carbon sources, so it makes sense for it to form the basis of our move away from natural gas.

The government has already stated that no new gas boilers will be permitted in new homes from 2025. Furthermore, dwellings built to the Future Homes Standard will be what the government terms ‘zero carbon ready’ so that they can make the most of low-temperature heating systems based on heat pumps. This will be reflected in the next iteration of Part L of the Building Regulations, which is due out in 2021.

It is relatively straightforward to change the design and operation of future homes through legislation. However, the numbers show that a sole focus on heating systems in new dwellings would not come close to achieving government heat pump installation ambitions. According to figures from the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, new house completions in England were around 160,000 per year in the three years up to 2020.

That figure is well below the number of installations required to hit the 600,000 target, which is where the process becomes more challenging. Persuading the nation’s homeowners to switch from their familiar gas boilers will be key to delivering real change in our domestic heating market.

The proposal is already creating discussion at national level. Issues around building services and heating systems don’t often make the pages of our national press. Yet newspapers such as the Daily Mail and The Telegraph have covered the government’s proposals on ‘banning’ gas boilers. Unfortunately, this has not always been in a positive light. Some articles have focused on the current disparity in pricing between gas boilers and heat pump systems, and others centred on how different the delivery of heat from the pumps is.

As members of the industry, we understand the benefits of heat pumps as a potential way forward for decarbonised heating and hot water systems. The question is, how do we explain these to the general public and persuade householders to adopt heat pumps in place of gas boilers?

Low carbon credentials are of course an important aspect of heat pump technology. This should certainly be a point in their favour as there is no doubt that consumers today are far more aware of environmental issues than previous generations. In research carried out for National Grid in 2020, 93% of respondents recognised that climate change is a serious or very serious issue.

The automotive industry is seeing the effects of this shifting opinion, with a significant uplift in sales of electric or hybrid cars, as drivers make the move to low carbon motoring. Government figures show that the UK is leading the way on the purchase of electric vehicles, with one in seven new car sales so far in 2021 having a plug.

But, while people are making the link between electric cars and reducing emissions, they are missing the message on home heat. In the National Grid survey, only 5% or respondents identified heat as a main contributor to the UK’s carbon emissions. They also felt that alternative heating technologies were ‘rarely advertised’. We have to ensure those technologies become as familiar to the general public as electric vehicles.

That said, it is important to look beyond ‘green credentials’ as the only reason to adopt new heating technologies. We need to develop a broader appeal if we are to win over householders. One way to do this is to take one of the so-called disadvantages of heat pumps and present it as a benefit.

It has been noted by the press that heat pumps have to be ‘on all of the time’, and that this is a disadvantage of the technology. This is in contrast with the traditional gas boiler, which appears to most householders to be on only when required.

There is a better way to explain this difference and to reassure potential heat pump buyers that the ‘always on’ approach is far better in terms of comfort, as well as efficiency and energy saving. Heat pumps can maintain a steady temperature a few degrees below ‘comfort’ level, for example 18ºC, which can quickly rise to a set-point of, say, 21ºC when required by the homeowner.

This ability to respond quickly to the needs of occupants can be enhanced by smart controls and sensors. These can detect outdoor temperatures, for example, and respond accordingly. So, if the outdoor temperature drops before space heating is due to increase to the required 21ºC first thing in the morning, the system will switch on earlier to ensure that the house is at the required temperature when residents are waking up in the morning.

Another benefit of heat pumps that should appeal to all energy bill payers is that this smarter level of control means they can take advantage of cheaper electricity tariffs. As more homes are connected to smart meters, it is much easier for homeowners to identify when they are being charged higher tariffs at peak times. A heat pump can help them to beat these higher costs by using electricity at off-peak times, saving significant sums on the household energy bill.

A trial project, named Optimised Forecasting for Switching Energy Tariffs (OFFSET), took place at the end of 2020. It tested a platform that automates control of heating systems (fully electric and hybrid heat pumps) and other smart appliances. Smart controls were used to shift the operational periods of these appliances to periods when electricity prices are lower. This not only lowered costs for householders, but also reduced peak demand and stress on the UK electricity grid.

The joint trial by Samsung, Passiv Systems, My Utility Genius, and BRE showed that potential savings from optimised heating control (compared to flat-rate tariffs) could be between £14 and £169 per year. It would also place half-hourly settlement energy pricing (currently only available to commercial customers) into the hands of householders.

While this was a test project, it demonstrates the flexibility that electrical heating, combined with smart controls, has the potential to offer consumers. And other benefits could soon be available to householders to help them make the decision to switch to heat pumps. For example, there are further energy and carbon savings to be made by combining a new heat pump system with solar photovoltaics (PVs) and battery storage. PVs are already a familiar cost-effective solution, and battery storage at household scale is slowly entering the market. Given the potential demand, it may not be too far-fetched to imagine that the technology will be widely available in just a few years.

The government has work to do to kickstart the transition to heat pumps. Not only does it have to consider the issue of financial incentives for homeowners, it also has to rebalance the price of electricity for consumers.

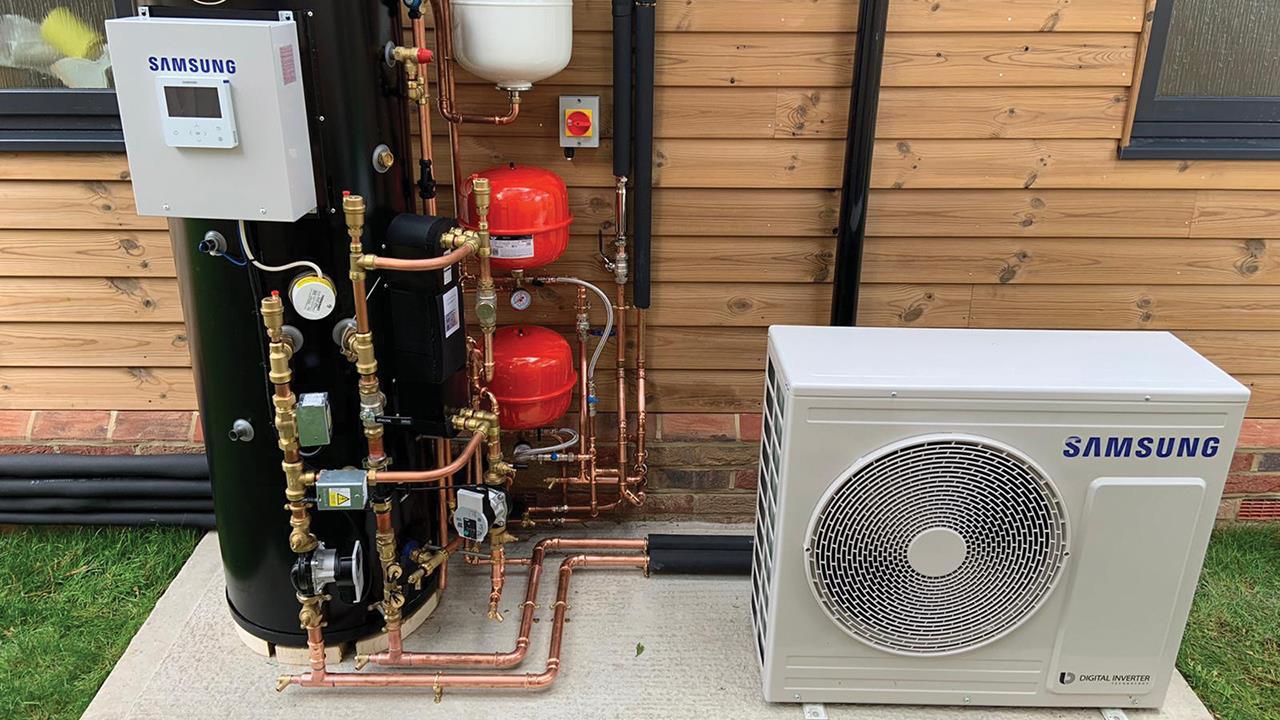

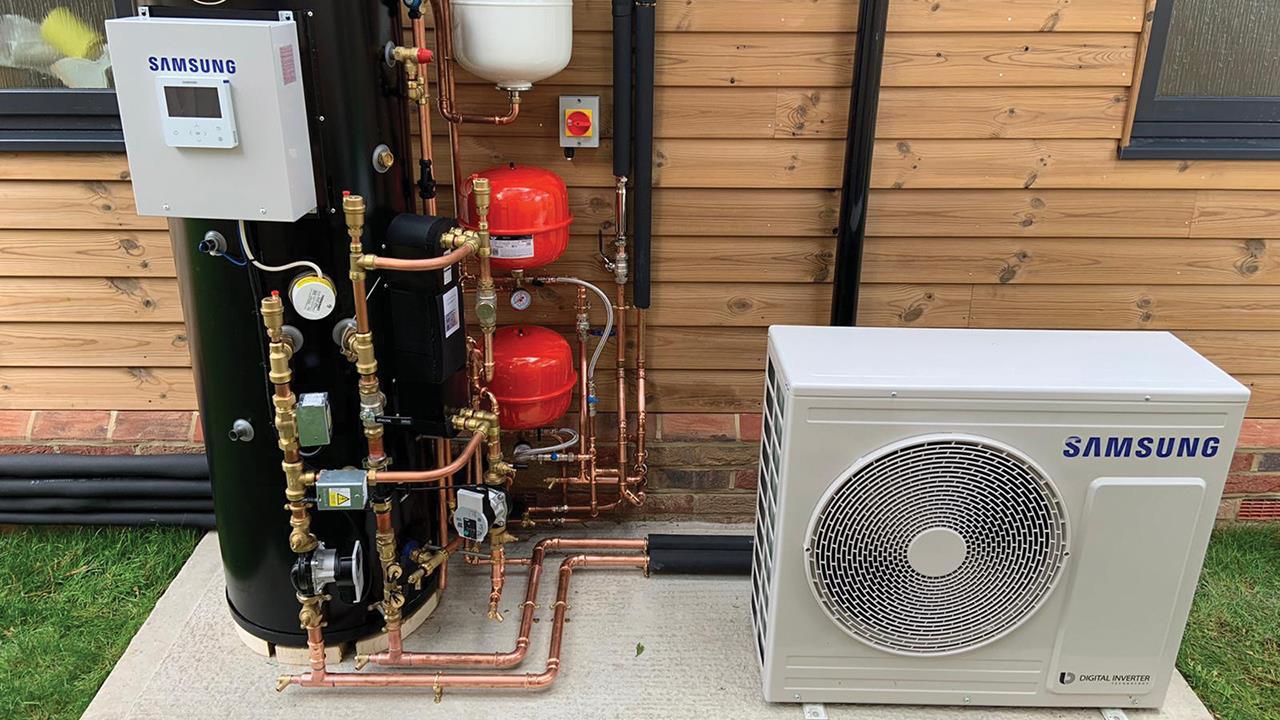

Much of the financial burden of our shift to a greener grid has been on electricity. Moving those higher costs to gas, to reflect its significantly larger carbon footprint, would certainly help persuade consumers to consider electric heating more readily. And, of course, we have to support training in our industry to ensure that the heat pump installer base is there to deliver good quality installations that are as reliable as gas boilers have been for so many years.

If the UK is to achieve this major change in how we heat our homes and ensure the UK meets its net-zero goals, then we all must work together to get the public on board for the journey.

If you'd like to keep up-to-date with the latest developments in the heating and plumbing industry, why not subscribe to our weekly newsletters? Just click the button below and you can ensure all the latest industry news and new product information lands in your inbox every week.