Having been a plumber for some 25 years, I’ve come across many unpleasant blockages and waste pipe issues in my time. While in most instances the blockages are due to some sort of accidental abuse, from excessive grease down a kitchen sink, to hair down a shower, or a little too much toilet paper or baby wipes down the WC, other times these are caused by a poor initial installation.

Regulations on how UK waste and drainage pipework is installed is quite clear when it comes to required gradients, diameter of pipework, and length of runs, etc. It is reassuring that the vast majority of UK plumbers know what can and can’t be done, and ultimately leave the customer with an installation that is fit for purpose and will give many years of satisfactory service.

However, unfortunately, sometimes there are exceptions and the concern for the customer is that he or she is at the mercy of the plumbers’ experience, knowledge, and ability. If there any corners that have been cut, or any oversight has occurred, these many not come to light until many weeks, months, or even years have passed.

In the USA, however, they arguably have a better system that goes a long way to safeguarding the customer, while ensuring the standard of plumbing remains more than acceptable. Following any plumbing works at a property that entails the running or rerunning of waste (or supply) pipework, a state or city-appointed plumbing inspector has to attend on-site to sign the works off before the plumber gets paid, or the walls, floors or ceilings can be closed.

Having followed several of these inspectors around various job sites, I can say that these guys are extremely sharp-eyed, and their knowledge of the industry ‘codes’ is impressive. They also take no prisoners.

I attended one bathroom installation where a shower waste had been trenched into a solid floor, but inbetween the plumber finishing and the inspector arriving, the builder and tiler got a little too excited and back-filled the trench and tiled the floor.

Although the inspector knew the plumber, he didn’t give him the benefit of the doubt and the builder was forced to excavate the floor so that visual access to the pipe could be gained and a ‘pass’ certificate be handed to the customer who, by this time, was in floods of tears. It was quite shocking to witness this situation unfolding but I can appreciate it was for the greater good.

The drawback to having to work with this procedure is time spent waiting for an inspector to attend on-site. However, in the Greater Los Angeles area, the time taken from booking to inspection is normally 2-3 days, and while for many in the UK this would create frustrating delays with the programme of works, in the USA they don’t know any different so they just accept it for what it is.

Having had some interesting and in-depth conversations with the inspectors, it is clear that, by their own admission, they focus more on the waste pipe aspect of the installation than the supply pipe because of the potentially higher cost to rectify the error. That’s not to say they don’t pay attention to supply pipework, but ‘code’ normally dictates that supply pipework has to be pressurised for 24 hours prior to inspection, by which time a leak should be obvious and easy to see. With waste pipes, not only are there visual inspections but also flow and air test inspections.

One thing I found interesting is that the ‘code’ dictates that all solvent fittings must be primed prior to using the solvent cement. There is really no way to ‘trick’ the inspector as the primer is normally bright pink, blue, or purple in colour, and is highly visible on the pipe that slides into the fitting. It becomes even more visible when you consider that 95% of USA waste pipes are white.

The inspectors encourage the plumbers not to be sparing with the primer and almost slosh it around to prove its existence within a joint; this will be seen with a quick passing glance as opposed to an intricate inspection.

Among other things inspectors are looking for is the correct inclusion of vent piping. I was surprised to find out that every water-using appliance that has a trap must have a standalone vent pipe or be linked to a vent that’s open to the atmosphere. Even a dishwasher and washing machine outlet must be vented up to above the roof; this explains why it is commonplace to see roofs on USA homes with sometimes four, five, or more vent pipes protruding through roof tiles (or shingles as they are commonly known).

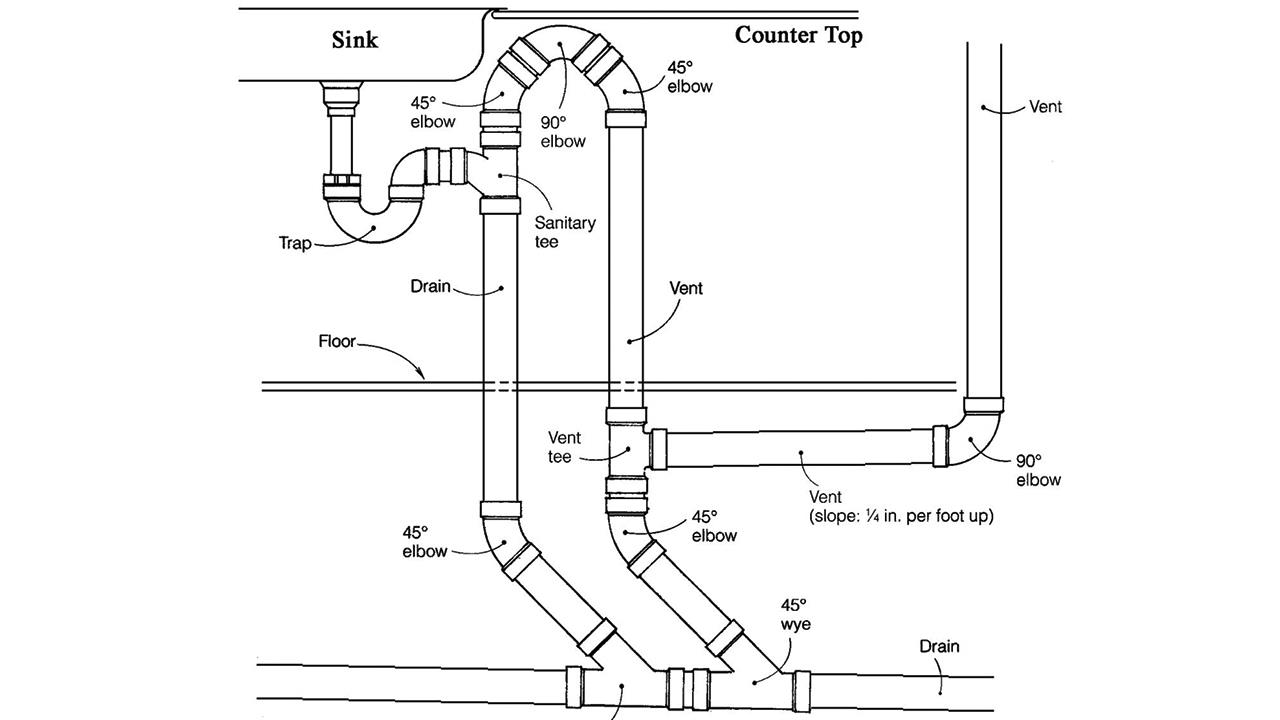

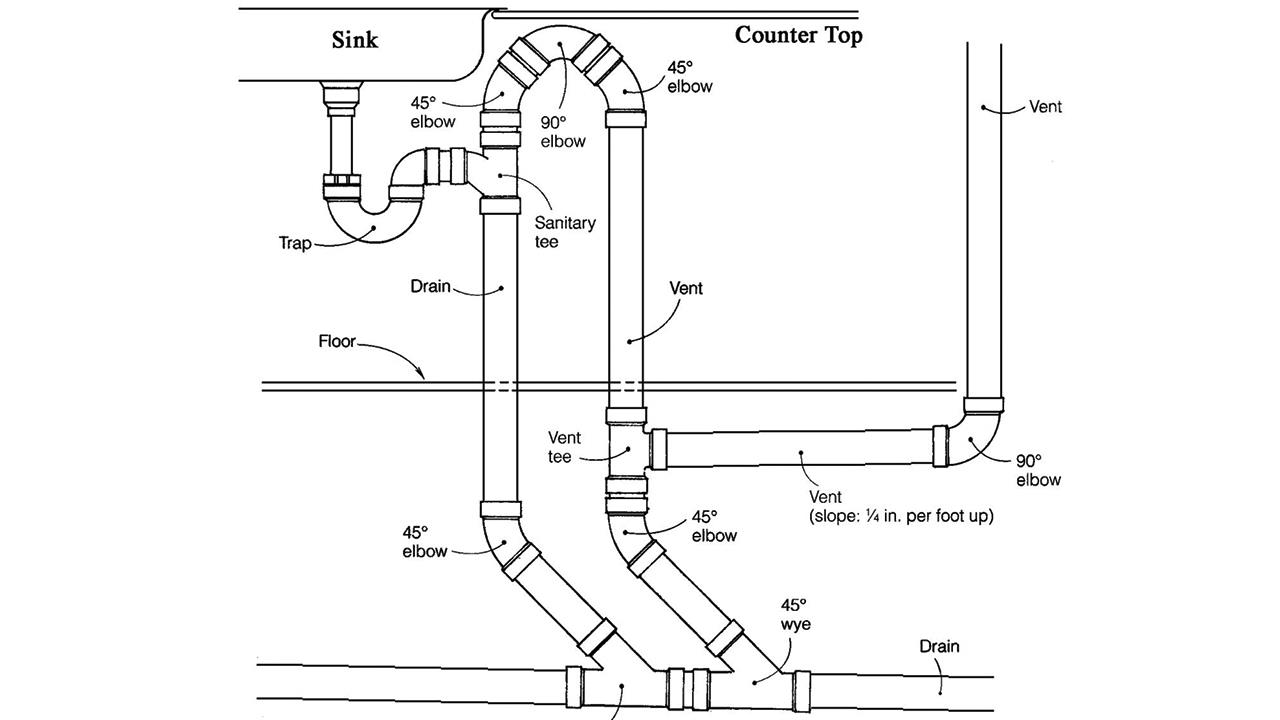

It’s true that the running of vent pipes almost equates to the amount of actual waste pipes being run, but you can almost guarantee that no American home will ever have a glugging trap! The only exception is found when plumbing in an island sink, where obviously a vent pipe cannot simply rise out of the worktop and head into the ceiling. In that case, a very unusual pipework arrangement (diagram below) is implemented, one that looks quite strange but seems to work.

Another common aspect of the code that can trip up some plumbers is ‘teeing’ a pipe into a horizontal waste pipe, whether from a bath, basin, sink, washing machine, or whatever. Instead of being allowed to use a branch fitting like our standard UK 92.5º tees, a ‘Y’ tee or 45º tee must be used in conjunction with a 45º elbow to ensure the water flows more easily and creates less turbulence at the junction.

In all my years when teeing into horizontal waste pipes, I have always just used a normal 92.5º tee, but having seen the emphasis that the US plumbing industry put on this, I think that if I ever returned to working as a plumber in the UK, I would probably take a leaf out of their book and do it their way!

If you'd like to keep up-to-date with the latest developments in the heating and plumbing industry, why not subscribe to our weekly newsletters? Just click the button below and you can ensure all the latest industry news and new product information lands in your inbox every week.