Neil Macdonald, Technical Manager at the Heating and Hotwater Industry Council (HHIC), looks at what could be taken on board when the Building Regulations Part L review is finalised.

With challenging energy-saving targets set for the next 30 years, the Building Regulations Part L review is a significant one that has the potential to make a real difference to how we build our homes, and also how we heat them.

There is no doubt that futureproofing our homes is vital. The Future Homes Standard, currently due for implementation from 2025, will aim to make our homes more efficient via cost effective, low carbon technologies, but in a way that is affordable for the end-user.

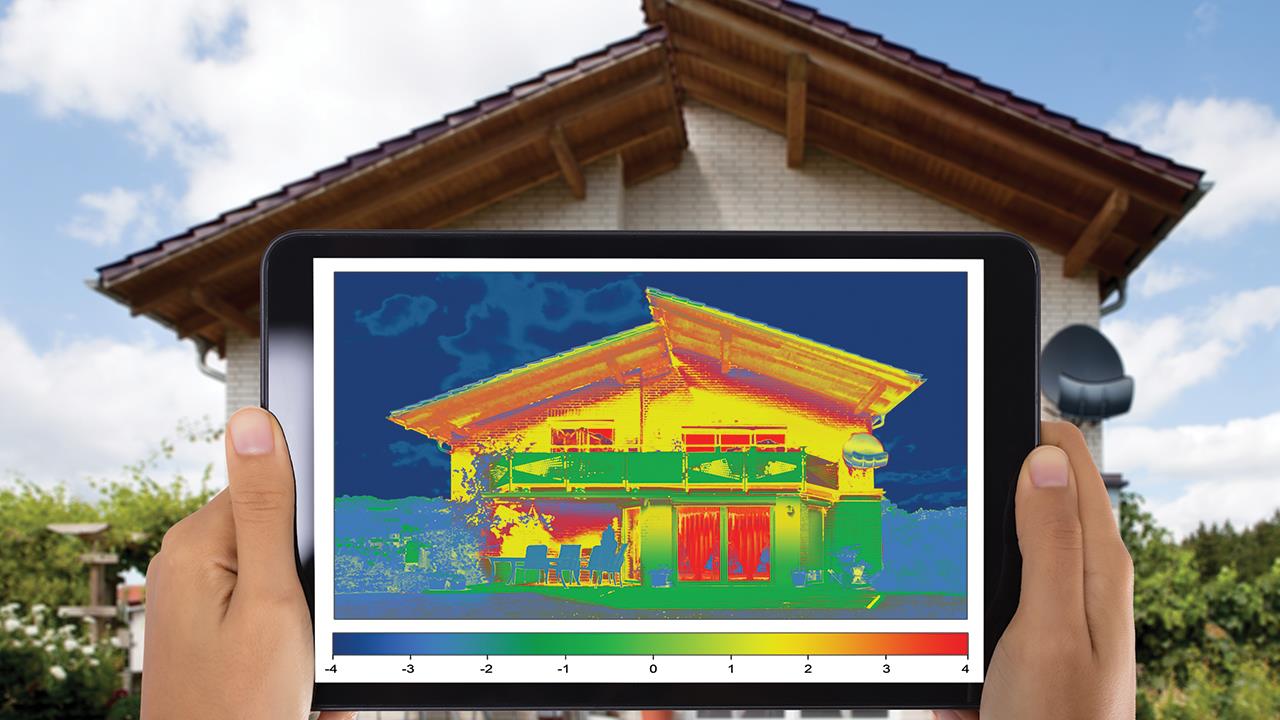

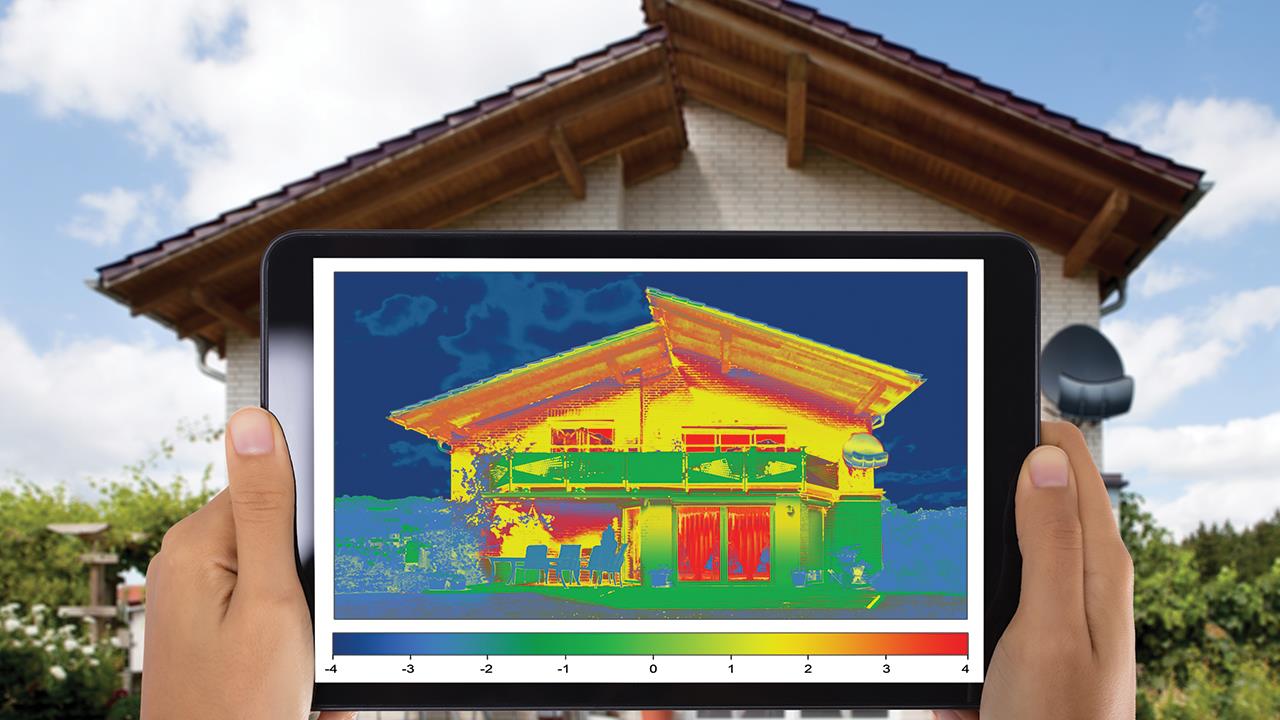

Within this, a ‘fabric first’ approach is essential if we are to get close to the challenging target of cutting emissions from our home energy use by half by 2030, and to net-zero by 2050. It stands to reason that measures to minimise our energy demand will, in turn, limit our overall usage and naturally increase our efficiency levels.

So, to get anywhere near the targets set, ambitious but, importantly, achievable fabric backstops need to be in place. This build standard will allow developers and specifiers to make the most of appropriate heating and ventilating technologies to suit the property characteristics and homeowner needs.

Therefore, we would question the government’s preferred 2020 uplift going down the route of setting less stringent fabric standards for the notional building, as this seems to move away from tackling energy demand at its root cause. The better the build of our homes, the less energy they will use and lose and, at present, important low carbon technologies may not fulfil their potential if the home is badly insulated.

The anticipated move to low temperature systems, and low-grade heat, seems to be a popular one, but consumer acceptance and perception may yet require some work. As a nation, we are predominately used to bi-modal heating patterns; putting the heating on if we are cold, and being able to instantly boost it when desired.

Many homeowners will simply not be familiar with continuous heating with night setback, as is commonplace in many parts of Europe, which may become necessary for future newbuild dwellings, even with a high standard of fabric performance. A likely risk, without further education, is unnecessary consumer interaction with the heating controls, i.e. altering optimised time/temperature settings, resulting in greater energy consumption and reduced savings.

Focus on 'as built' performance

When we consider the ‘as built’ performance of homes, compared to design and specification, there are concerns around delivering low carbon heat en-masse and too quickly. It has to be done correctly, to the highest standards, and with tangible results, or we risk undermining public confidence due to negative experiences by early adopters (i.e. those purchasing new homes built to the new standards).

This raises the issue of timing. While the HHIC wholeheartedly agrees with the 2025 Future Homes Standard’s ambition, this is a large industry and many bridges will need to be crossed in terms of scaling product, supply chains, and installation skills. Current timelines being suggested are already very tight and run the risk of leaving the industry with little time to plan.

More time to prescribe the detail of the 2025 Future Homes Standard, in part based on 2020 uplift feedback from industry, may be needed to ensure the mark isn’t missed unnecessarily and due only to short timescales.

By way of balance, while a switch to electric across everything from cars to public transport to heating sounds progressive and has undoubted appeal, SAP assumptions around the carbon intensity of grid electricity must also be grounded in fact. As more heat demand is met by electricity, this will inevitably increase the load on the grid.

With renewable electricity generation intermittent by nature, including the growth of local on-site generation such as solar PV, short to mid-term this capacity will generally be met by flexible gas generation, but with resultant carbon emissions potentially not accounted for in the proposals.

It is our view that favourable SAP assumptions must always be reconciled with the ‘actual’ carbon emissions likely to be realised. We do not see a risk-averse approach here, which is also mirrored in the impact assessment costings, but we fear the cost boundaries do not fully reflect the need for expenditure to augment the local electricity supply infrastructure.

A final point worth mentioning is the issue of regional disparity and that, across the industry, there is support for restricting individual local authorities’ ability to set higher targets. While this might at first appear counter-intuitive to some, our belief is that we should aim to substantially raise the bar, but collectively.

This would allow the industry to plan nationally, including housebuilders, who will importantly be tasked with delivering the new homes to be built to the new standards. This approach allows all parties to build and scale the required supply chains with certainty, and so lessens the risk of not delivering national targets on time and to standard, due to servicing multiple, bespoke regional specifications.

We are well on the road to a low carbon future. Yet, there are so many factors called into play along the way, from supply to acceptance, and a willingness to change. Getting the basics right from the outset will be vital. The changes to Part L have the opportunity to present well-thought through, deliverable aims that can be actioned to the highest standard and bought into by end-users to see us move closer to the Future Homes Standard goal.

We anticipate a government response to the consultation, and subsequently firmer indications of what the Future Homes Standard will look like later this year.

If you'd like to keep up-to-date with the latest developments in the heating and plumbing industry, why not subscribe to our weekly newsletters? Just click the button below and you can ensure all the latest industry news and new product information lands in your inbox every week.